It is the very process of actually making something with one’s hands that we believe leaves room for inspiration. Model making allows for “happy mistakes,” breakthroughs that originate in the non-verbal part of the mind. That just doesn’t happen when using a computer.

With all of the technological advancements in the architecture field in recent years, including the ability to make 3D-printed models, CAD drawings and highly detailed renderings, one may wonder why architecture firms and architectural degree programs still rely so heavily on the practice of hand-making physical models. There are a number of reasons why model making is still beneficial to architects, students and clients alike. Physical models present a means of communicating and exploring spatial interrelationships, scale, materiality and other design considerations. Models allow us to understand and imagine a finished space in ways that two-dimensional drawings cannot. And most importantly, it is the very process of actually making something with one’s hands that we believe leaves room for inspiration. Model making allows for “happy mistakes,” breakthroughs that originate in the non-verbal part of the mind. Reverie is as important as technology.

In his book, Architectural Modelmaking, architect Nick Dunn states that architectural models “enable the designer to investigate, revise and further refine ideas in increasing detail until such a point that the project’s design is sufficiently consolidated to be constructed.” In other words, models serve as an invaluable learning tool for architects, allowing them to explore various design iterations in a tangible way. Building a scale model is undoubtedly time consuming, but the process helps create an awareness and deeper understanding of the intricacies of the project as well as the construction process— something that digital tools don’t necessarily allow.

Physical architectural models also act as perfect communicative devices for clients, allowing them to have a much better understanding and visualization of the project.

The practice of building architectural models is one that dates back to ancient times. In ancient Egypt, small carved stone models were buried with the deceased to give them a place to reside in the afterlife. These models give us a glimpse into the architectural practices of ancient Egypt and the way their dwellings would have appeared. According to Miriam Stead in her book Egyptian Life, the architectural models “are also very interesting for archaeologists, who can use them to interpret representations of houses in tomb scenes, and the remains found in ancient towns. The conventions of Egyptian art, in which all objects are shown in their most recognizable form, mean that houses are represented in a very schematized way.”

In ancient Incan Peru, the intricately carved Sayhuite boulder, dating back some 600 years, includes such details as irrigation ditches and canals, mountains, waterways and animals. The stone gives us information about the architecture, engineering and sophisticated irrigation systems developed by the Incas.

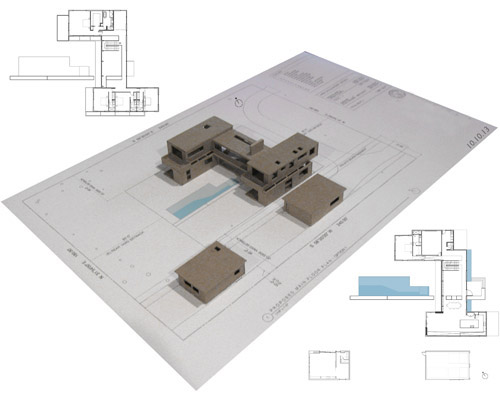

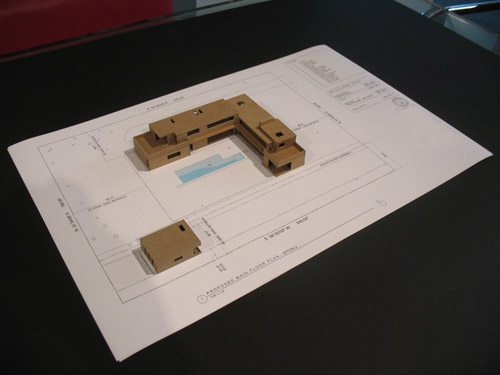

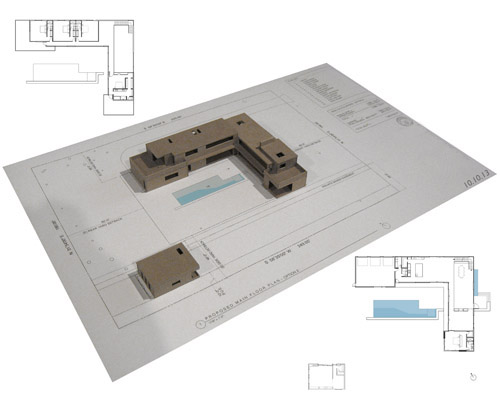

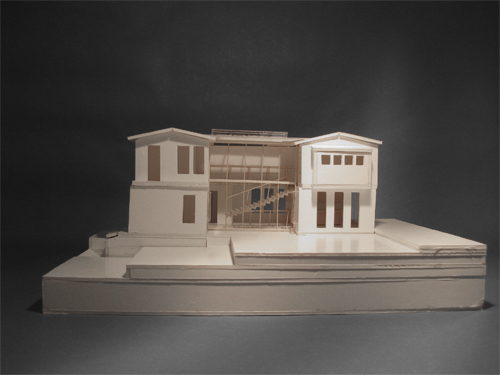

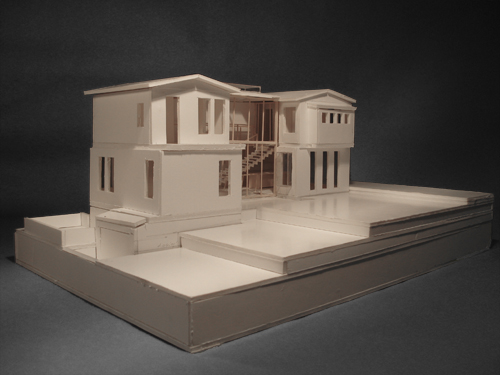

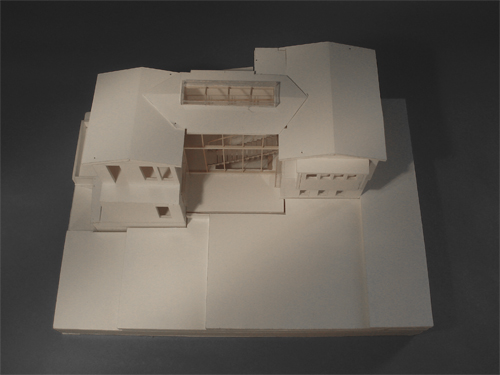

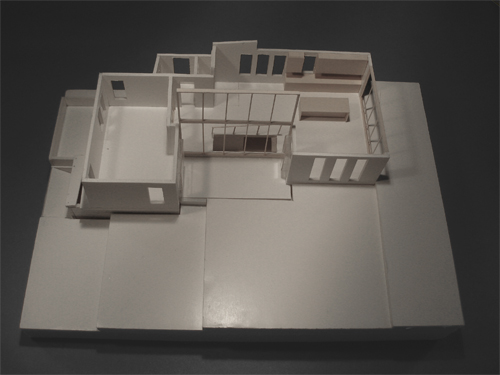

Atherton House

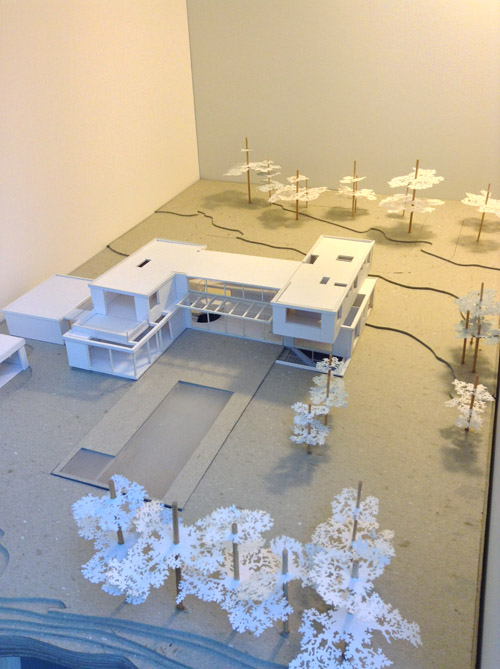

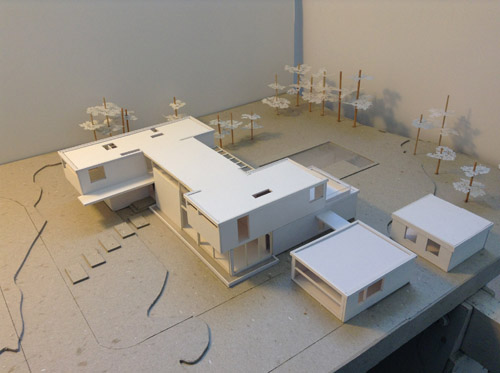

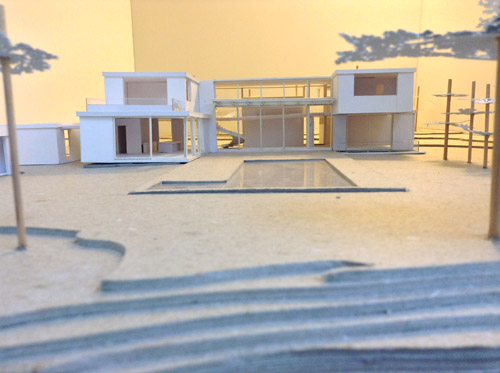

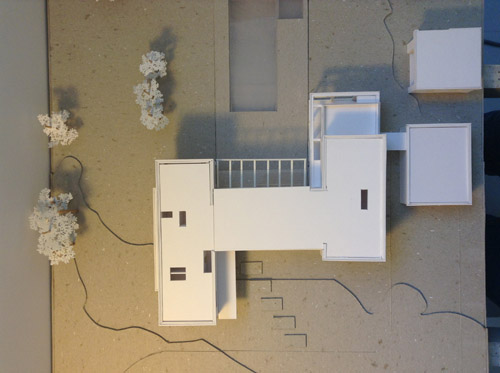

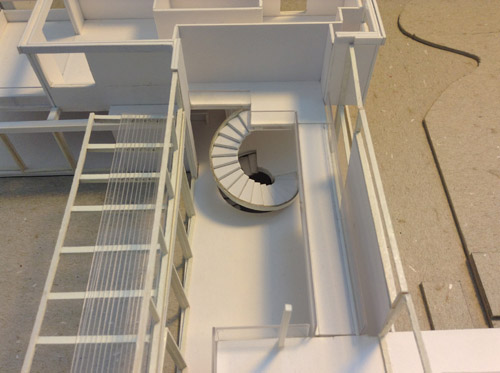

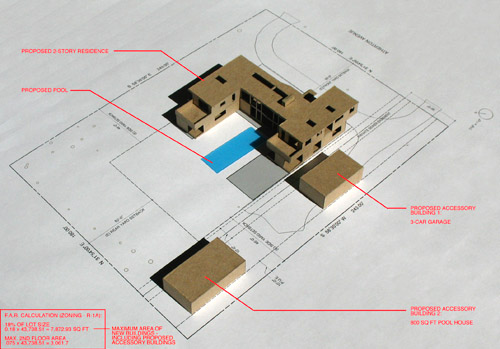

This project is a new modern house on an acre lot in Atherton, CA. The house consists of two wings which are connected by a bridge over a large central open space with a spiral staircase. Shifting volumes provide cantilevers and the opportunity for skylights where the volumes slide over each other. Several huge glass sliding doors allow the house to open up to the back patio and pool, creating a strong indoor-outdoor connection.

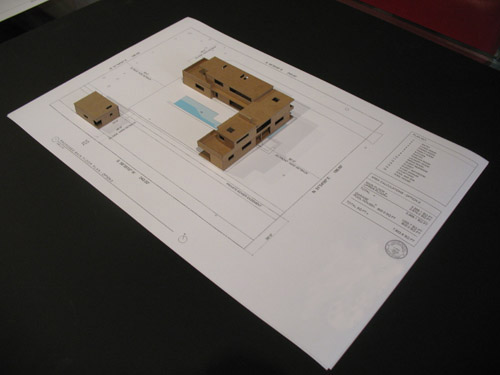

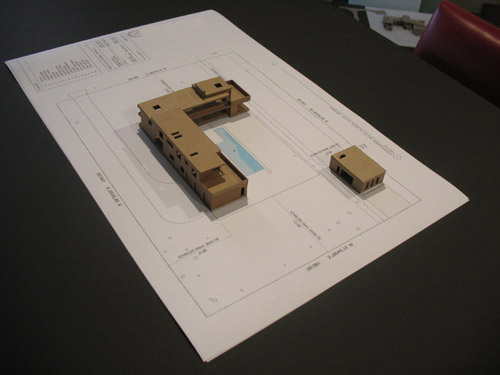

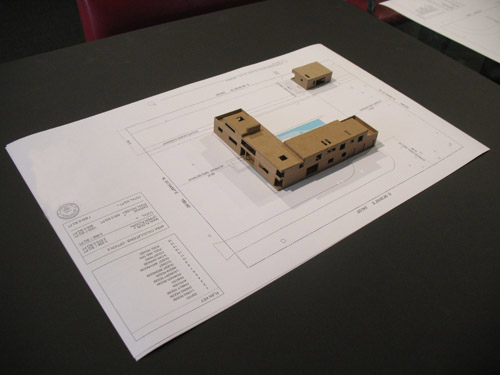

Small-scale models were used to explore floor plan options with our clients. Each model explains different choices in layout and massing in the clearest way possible:

Proposed Model. Clockwise: 3-story Residence, Accessory Building: 3-Car Garage, Accessory Building: 800 Sq Ft Pool House, Pool

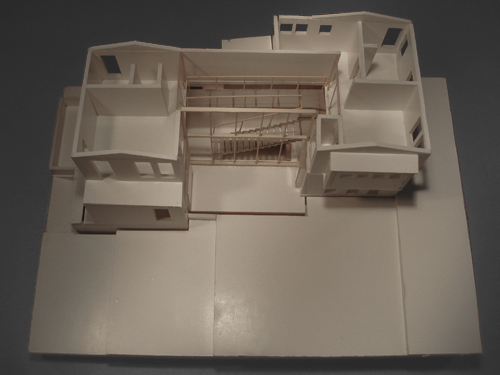

Once a floor plan was selected, a larger, more detailed model was constructed and presented:

Green Street House

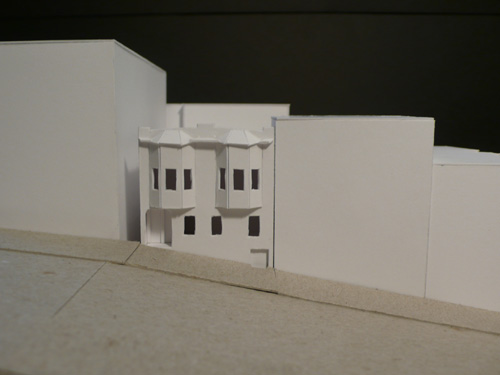

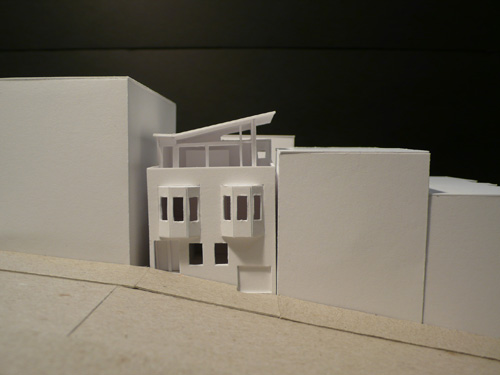

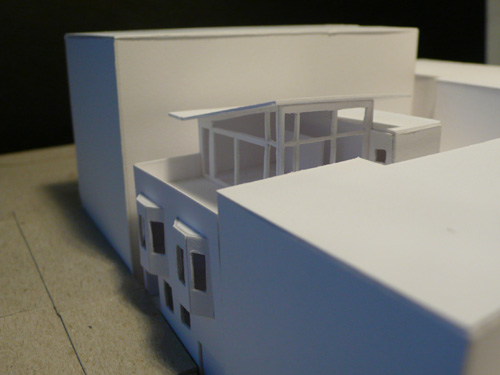

The Green Street House, San Francisco, is one of a pair of cottages designed by architect Elizabeth Austin in 1917. The building is a historic resource, and as such, the exterior of the house is sacred. The models allowed us to re-imagine dramatic changes to the interior, as well as possible façade changes.

Initial Model:

Final Model:

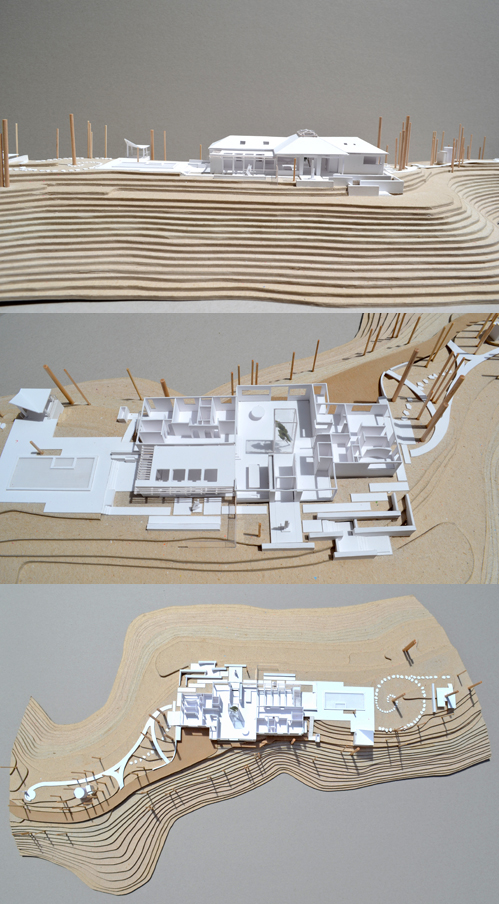

Greenwood/Monte Sereno House

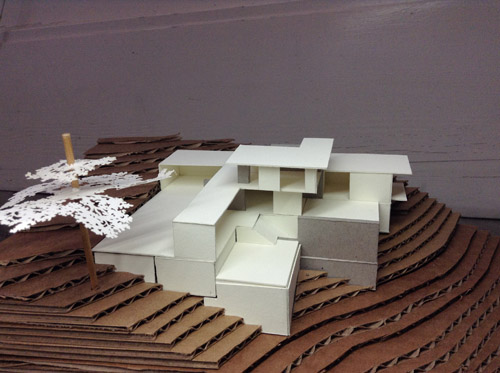

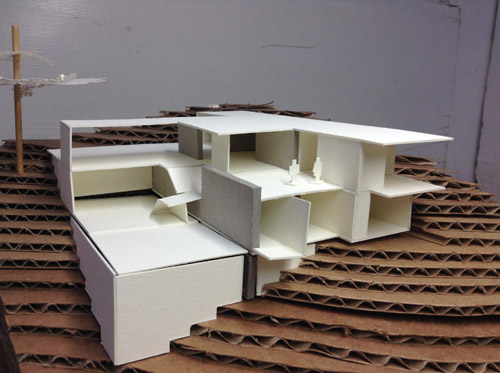

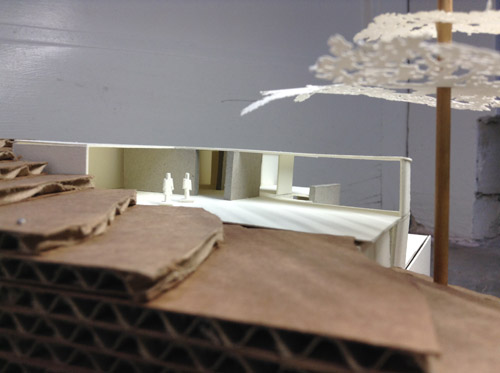

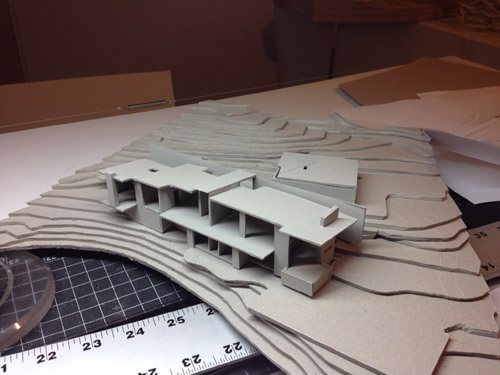

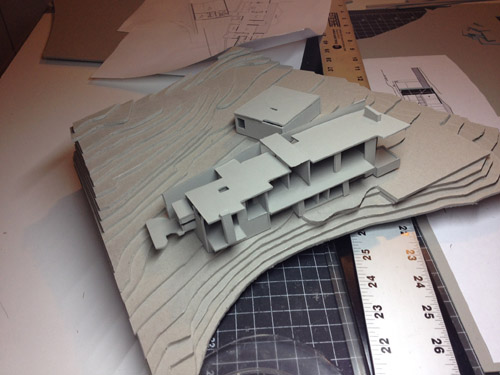

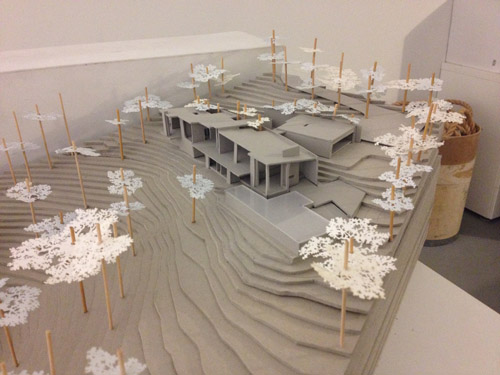

The Greenwood Residence is a new hillside home designed for an extended, multigenerational family. The house was designed in model form on a topographical model base, without floor plans or other drawings. After we were convinced of the massing and form, the plans were developed in the computer.

Portola Valley House

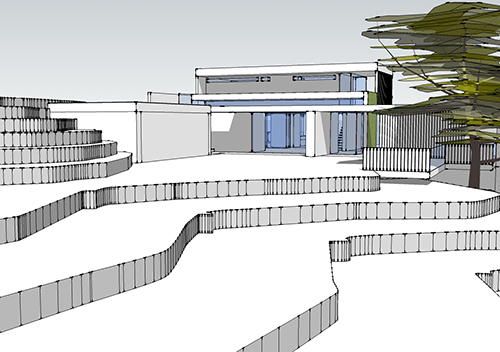

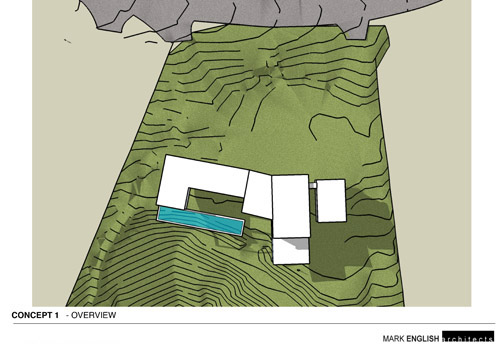

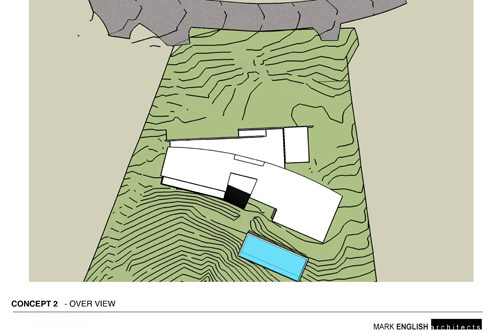

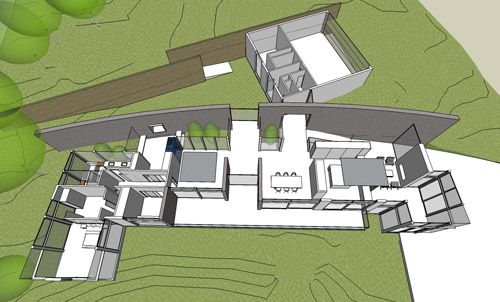

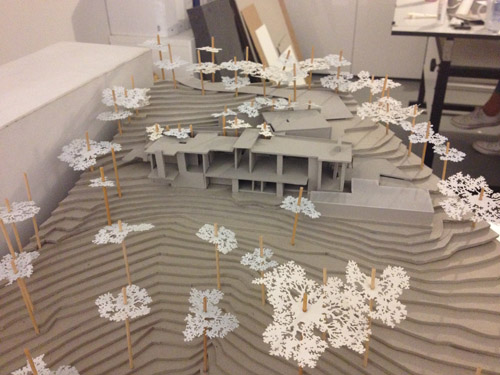

The Portola Valley Home is another hillside house grown from the topography. The evolution of the layout started with a curving gesture along the slope, culminating in the major public space, focused towards the location of Mt. Diablo on the horizon. Again, the design was explored in model form well before floor plans or other drawings were developed.

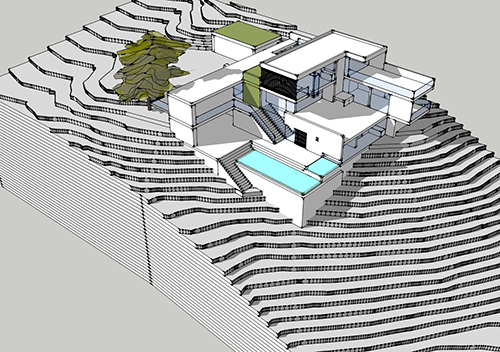

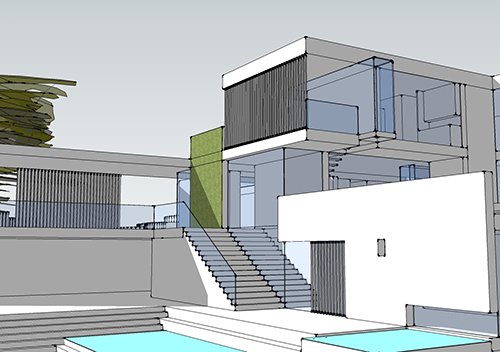

Design Model:

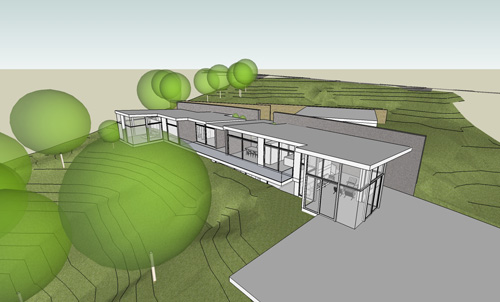

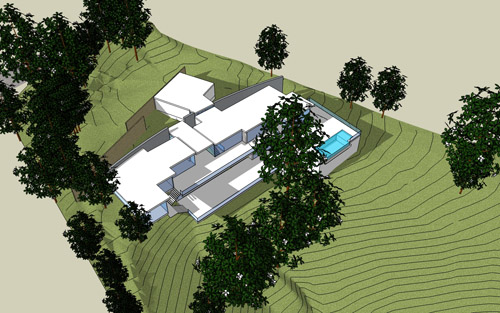

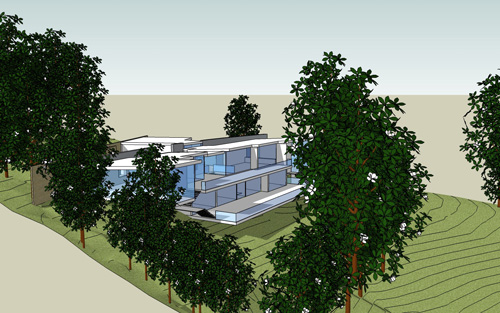

Sketch-Up Models:

Final Model:

Montgomery House

The Montgomery Apartment Building is in a very different context than the previous examples. Here the topography is human-made in the form of existing buildings. The model allows us to share the nature of the sculptural change in the neighborhood that our proposal would create.

Existing Massing Model:

Remodel/Addition:

Saratoga House

The Model Making Process:

“Because most of our time is spent creating 2-D drawings, taking the time to realize those drawings in 3-D form allows you to make better design decisions and gives you a better understanding of the scale of the project and how the spaces relate to each other. It also definitely teaches you patience. It helps people who don’t work in the field have a better understanding of the project and it piques their interest”—Adrienne, designer at Mark English Architects