WORK EVERY WAKING HOUR - Elon Musk (Motivational Video)

The following post is a guestpost by Walter Chen, founder of a unique new project management tool IDoneThis. More about Walter at the bottom of the post.

So, here is the thing right at the start: I’ve always been uncomfortable with the traditional ideal of the professional — cool, collected, and capable, checking off tasks left and right, all numbers and results and making it happen, please, with not a hair out of place. An effective employee, no fuss, no muss, a manager’s dream. You might as well be describing an ideal vacuum cleaner.

I admit that I’ve never been able to work that way. There is one thing that always came first and most importantly for me: How am I feeling today? I found that it can easily happen to think of emotions as something that gets in the way of work. When I grew, I often heard that they obstruct reasoning and rationality, but I feel that we as humans can’t shut off our humanness when we come to work.

Feelings provide important feedback during our workday. It doesn’t make sense to pretend that it’s best or even possible to keep our emotions and work separate, treating our capacity for emotion and thought as weakness. I wanted to look into whether there was anything besides a gut feeling to my suspicions behind keeping the head and the heart separate in business.

What does emotion have to do with our work?

It turns out, quite a lot. Emotions play a leading role in how to succeed in business because they influence how much you try and this is widely misunderstood by bosses and managers.

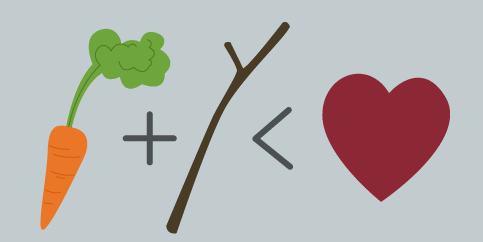

Psychologists Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer interviewed over 600 managers and found a shocking result. 95 percent of managers misunderstood what motivates employees. They thought what motivates employees was making money, getting raises and bonuses. In fact, after analyzing over 12,000 employee diary entries, they discovered that the number one work motivator was emotion, not financial incentive: it’s the feeling of making progress every day toward a meaningful goal. In Fact, Dan Pink found that actually the exact oposite is true:

In the famous expriment by Dr. Edward Deci clarified again whether emotional feedback or money would engagement with work. People were sitting in a room and tried to solve a puzzle while Deci measured how much time they put in, before giving up. For Group A, he offered a cash reward for successfully solving the puzzle, and as you might expect, those people spent almost twice as much time trying to solve the puzzle as those people in Group B who weren’t offered a prize.

A surprising thing happened the next day, when Deci told Group A that there wasn’t enough money to pay them this time around: Group A lost interest in the puzzle. Group B, on the other hand, having never been offered money in exchange for working on the puzzles, worked on the puzzles longer and longer in each consecutive session and maintained a higher level of sustained interest than Group A. So if it not money what else really motivates us?

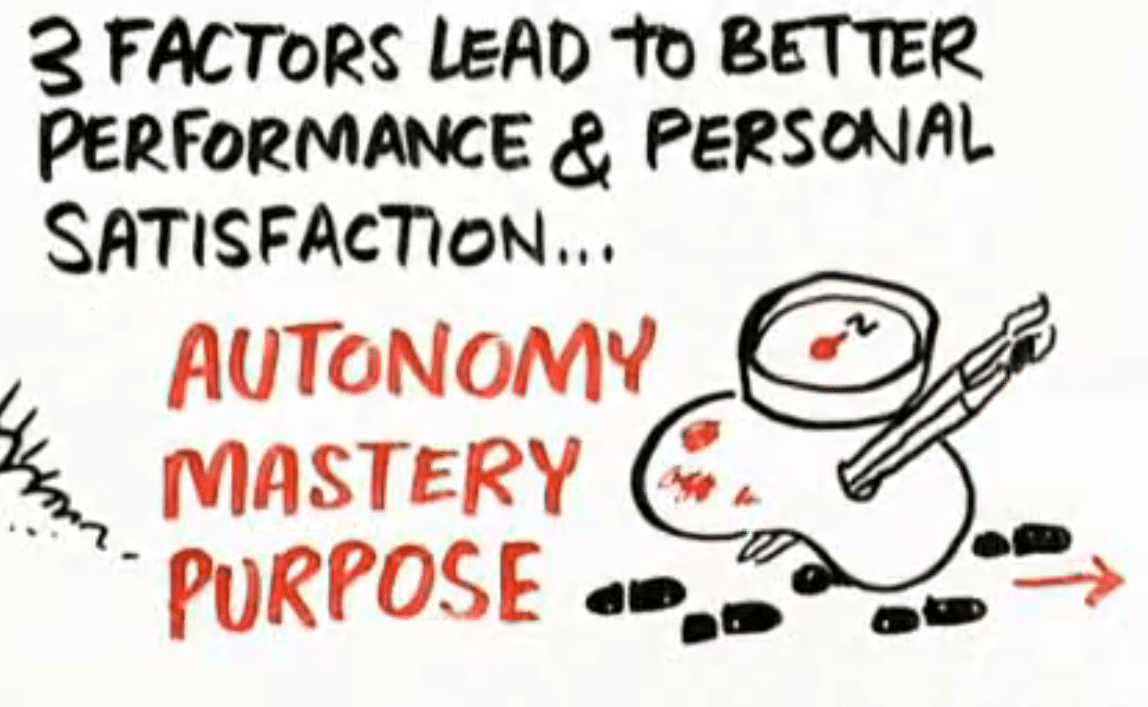

The 3 real reasons that motivate us to work hard every day

Pink explains further that there are in fact just 3 very simple things that drive nearly each and everyone of us to work hard:

- Autonomy: Our desire to direct our own lives. In short: “You probably want to do something interesting, let me get out of your way!”

- Mastery: Our urge to get better at stuff.

- Purpose: The feeling and intention that we can make a difference in the world.

If these three things play nicely together, Amabile and Kramer called this the somewhat obvious “inner work life balance” and emphasize its importance to how well we work. Inner work life is what’s going on in your head in response to workday events that affects your performance.

The components of the inner work life — motivation, emotions, and perceptions of how the above three things work together — feed each other. So ultimately our emotional processes ultimately our motivation to work. They end up being the main influencer of our performance.

Deci’s experiment showed that payment actually undermined intrinsic motivation because such external rewards thwart our “three psychological needs — to feel autonomous, to feel competent and to feel related to others.” As he told BBC.com, “You need thinkers, problem solvers, people who can be creative and using money to motivate them will not get you that.”

What’s going on inside our brains that connects our emotions to motivate you as a thinker and problem solver?

Amabile and Kramer tell us this: